Candace Kang, Ph.D.

Abstract

This article explores explores the reasons why radiocarbon dating methods face insurmountable challenges when applied to dinosaurs. Despite the precision achieved in various archaeological contexts, the claims of antiquity to the purported fossils of dinosaurs pose formidable hurdles that would impede accurate dating.

Paleontology, as a discipline, hinges on the verifiable nature of fossil evidence. Dinosaur fossils, often considered emblematic vestiges of Earth’s ancient fauna, have been subject to pervasive scrutiny, occasionally accompanied by skepticism regarding their authenticity (Schweitzer et al., 2005). This skepticism, rooted in diverse scientific and public discourses, prompts a meticulous examination of the methodologies underpinning their temporal attribution.

This article undertakes an exploration of the intersection between radiocarbon dating and dinosaur paleontology. By dissecting the assumptions inherent in radiocarbon dating and juxtaposing them against the ostensibly fantastical realm of dinosaurs, we aim to scrutinize the authenticity of dinosaur fossils (Sjövold, 1986). This critical analysis extends beyond mere skepticism, delving into the methodological intricacies that underscore the reliability of radiocarbon dating applied to specimens of such antiquity (Taylor & Bar-Yosef, 2014).

The rationale behind this inquiry is grounded in the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of the limitations and potential biases within radiocarbon dating methodologies. By evaluating the challenges posed by dating materials of immense temporal depth, we seek to contribute nuanced insights that transcend conventional narratives surrounding the application of radiocarbon dating to dinosaur fossils (Higham, 2011).

In the subsequent sections, we navigate the historical context, theoretical foundations, and contemporary perspectives shaping this discourse. Through a rigorous examination of both radiocarbon dating and dinosaur paleontology, we endeavor to unravel the complexities enveloping Earth’s ancient history, fostering a scientific dialogue that enriches our understanding of paleontological temporal frameworks.

Fundamentals of Radiocarbon Dating

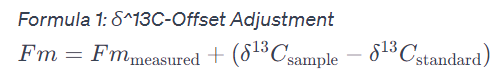

The temporal unraveling of carbon-14 transpires through the decay equation, a mathematical representation capturing the essence of radioactive decay. The equation, N(t) = N₀e^(-λt), delineates the proportion of remaining carbon-14 (N(t)) concerning the initial quantity (N₀), the elapsed time (t), and the decay constant (λ) (Bakaç, Taşoğlu, & Uyumaz, 2011). As time progresses, the number of carbon-14 isotopes diminishes, giving rise to nitrogen-14 in a process known as beta decay. This equation serves as the cornerstone for establishing chronological frameworks in radiocarbon dating, providing a roadmap for understanding the age of ancient specimens (Hamawi, 1971).

N(t) = N₀e^(-λt), delineates the proportion of remaining carbon-14 (N(t)) concerning the initial quantity (N₀), the elapsed time (t), and the decay constant (λ) (Bakaç, Taşoğlu, & Uyumaz, 2011). As time progresses, the number of carbon-14 isotopes diminishes, giving rise to nitrogen-14 in a process known as beta decay. This equation serves as the cornerstone for establishing chronological frameworks in radiocarbon dating, providing a roadmap for understanding the age of ancient specimens (Hamawi, 1971).

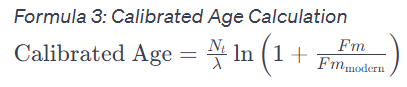

Central to the narrative of radiocarbon dating is the concept of half-life (t₁/₂), a characteristic property of radioactive isotopes. The half-life of carbon-14, approximately 5730 years, delineates the temporal constraints of this dating method. The ramifications of this finite half-life become apparent when dealing with samples from epochs distant in time, such as the Mesozoic era.

Fossils with an antiquity spanning millions of years introduce complexities. The finite half-life poses challenges in capturing accurate temporal information, especially when the temporal resolution required is on the geological scale. In the subsequent sections, we navigate through these challenges, exploring the complications that arise when applying radiocarbon dating to specimens as ancient as so-called dinosaurs.

The Challenges of Dinosaur Fossils

The application of radiocarbon dating to purported fossils is met with challenges that demand a rigorous assessment of existing paradigms. This section critically examines key impediments, casting a discerning eye on the traditional approaches employed in dating these enigmatic specimens.

One of the primary hurdles in utilizing radiocarbon dating for presumed dinosaurs lies in the pervasive lack of preserved organic material. Unlike more recent archaeological finds, Mesozoic fossils often exhibit a dearth of intact biological remnants (Nielsen-Marsh, 2002). This paucity raises fundamental questions about the veracity of applying radiocarbon dating, a technique reliant on the presence of organic matter. The limited availability of pristine specimens challenges the foundational assumptions that underpin radiocarbon dating theories. Without unequivocal evidence of well-preserved organic material, the reliability of dating outcomes becomes untenable (Gillespie, 1984).

Contamination issues and diagenesis introduce complexities into the radiocarbon dating process for alleged dinosaur fossils. Critics argue that geological processes and alterations associated with diagenesis can compromise the accuracy of dating outcomes (Hedges et al., 1995). Skeptics contend that foreign carbon introduced through contamination during excavation, handling, or subsequent storage can skew results. The meticulous sample selection and pretreatment procedures advocated in radiocarbon dating may inadvertently contribute to uncertainties, warranting a closer examination of the potential pitfalls inherent in these processes (Higham et al., 2006).

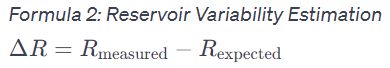

While the geological context is acknowledged as an influencing factor in radiocarbon dating outcomes, skeptics subject this relationship to critical scrutiny. Some argue that intricate geological anomalies may serve as convenient explanations for inconsistencies rather than genuine influences on radiocarbon ratios. Reservoir effects, often cited to explain variations in dating results, are viewed with skepticism, with critics positing that these effects may be more indicative of the geological milieu than conclusive evidence of ancient purported dinosaur fossils (Zoppi et al., 2004). In this nuanced examination, geological complexities emerge as factors that demand meticulous consideration in interpreting radiocarbon dating results, urging researchers to navigate the delicate balance between acknowledging geological influences and maintaining the integrity of the dating process.

Contamination issues and diagenesis introduce complexities into the radiocarbon dating process for dinosaur fossils. Critics argue that geological processes and alterations associated with diagenesis can compromise the accuracy of dating outcomes. Skeptics contend that foreign carbon introduced through contamination during excavation, handling, or subsequent storage can skew results. The meticulous sample selection and pretreatment procedures advocated in radiocarbon dating may inadvertently contribute to uncertainties, warranting a closer examination of the potential pitfalls inherent in these processes.

While the geological context is acknowledged as an influencing factor in radiocarbon dating outcomes, skeptics subject this relationship to critical scrutiny. Some argue that intricate geology may serve as convenient explanations for inconsistencies rather than genuine influences on radiocarbon ratios (Mann, Davis, & Herzfield, 1993). Reservoir effects, often cited to explain variations in dating results, are viewed with skepticism, with critics positing that these effects may be more indicative of the geological milieu than conclusive evidence of ancient dinosaur fossils. In this nuanced examination, geological complexities emerge as factors that demand meticulous consideration in interpreting radiocarbon dating results, urging researchers to navigate the delicate balance between acknowledging geological influences and maintaining the integrity of the dating process.

Preservation and Decomposition Dynamics in Geochronology

In scrutinizing the viability of radiocarbon dating for alleged dinosaurs, a comprehensive exploration of preservation and decomposition dynamics unveils intricate temporal nuances that challenge conventional wisdom.

The turnover rates of organic carbon, a linchpin of radiocarbon dating, present a multifaceted challenge when applied to presumed dinosaur fossils. Skeptics argue that the presumed temporal stability of organic material, foundational to radiocarbon dating’s reliability, encounters substantial obstacles in the context of alleged dinosaurs (Hedges, 2002). The protracted periods associated with fossilization suggest that organic carbon turnover rates may not conform to the conventional understanding derived from more recent archaeological samples. This disjuncture prompts skeptics to question the applicability of carbon dating methodologies calibrated for shorter turnover intervals, necessitating a reevaluation of temporal dynamics inherent in alleged dinosaur fossilization (Collins et al., 2002).

Sedimentary environments, integral to the fossilization process, wield considerable influence over preservation dynamics. Skeptics contend that the diverse array of sedimentary contexts in which presumed dinosaur fossils are discovered introduces variability in preservation conditions (Trueman & Martill, 2002). This variability, skeptics argue, challenges the homogeneity assumed in radiocarbon dating models. The relationship between sedimentary compositions and preservation mechanisms becomes a focal point for those questioning the universality of radiocarbon dating’s application to alleged dinosaur fossils (Berna et al., 2004). By delving into the specifics of sedimentary influences on preservation, skeptics aim to explain what may be obfuscating precise dating outcomes.

The prolonged durations associated with presumed dinosaur fossilization pose a unique temporal challenge for radiocarbon dating methodologies. Skeptics posit that the extended processes involved in fossilization may lead to unconventional preservation scenarios, where organic material undergoes transformations not accounted for in existing dating paradigms (Schweitzer, 2011). The chronological disjunction between the demise of the alleged dinosaurs and the discovery of their fossils prompts skeptics to scrutinize the assumption of temporal coherence underpinning radiocarbon dating (Poinar et al., 1996). By confronting the temporal intricacies introduced by prolonged fossilization, skeptics advocate for a nuanced understanding of preservation dynamics to refine the applicability of radiocarbon dating in the realm of presumed dinosaurs.

Calibration and Reservoir Challenges in Geochronology

Skeptics scrutinize the challenges posed by calibration curve complexities when attempting to establish precise chronological frameworks for alleged dinosaurs. One of the primary contentions skeptics pose involves the varied reservoir effects within ancient ecosystems housing alleged dinosaurs. Unlike more recent samples with established baseline data, presumed dinosaur fossils often emerge from environments where reservoir effects are not only diverse but also challenging to quantify accurately (Ascough et al., 2005).

The skepticism lies in the assumption that conventional calibration curves, derived from contemporary settings, might not seamlessly apply to the unique environmental contexts that sustained alleged dinosaurs (Reimer et al., 2004). Skeptics argue that the incorporation of varied reservoir effects demands a meticulous reassessment of calibration protocols, urging researchers to acknowledge the complexities inherent in ancient ecosystems (Walker, 2005). By highlighting the potential for carbon-14 to be sequestered or cycled differently in Mesozoic environments, critics point to the “old carbon” effect, where organisms ingest carbon from sources already depleted of the isotope, potentially yielding ages that do not reflect the specimen’s true chronology (Deevey et al., 1954).

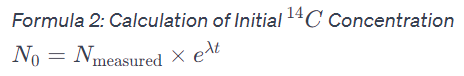

In the quest for precision, skeptics emphasize the intricate task of determining the initial C-14 concentrations crucial for reliable radiocarbon dating. Alleged dinosaur fossils, subjected to prolonged diagenesis, may undergo isotopic alterations that confound attempts to ascertain the original C-14 content (Geyh, 2001).

Skeptics contend that the reliability of the dating process hinges on accurate estimations of the initial C-14 concentrations, and any deviations introduce uncertainties that reverberate throughout the chronological framework (Aitken, 2014). The inherent challenges in isolating and measuring the pristine C-14 values within the alleged dinosaur fossils underscore the necessity for advanced methodologies and meticulous attention to detail. This is particularly relevant when considering the “background” levels of radiation; as samples approach the limits of the technique (roughly 50,000 years), the presence of even a single atom of modern carbon can dramatically skew the perceived age of a presumed ancient specimen (Plastino et al., 2001).

Furthermore, the potential for in situ production of C-14 within the burial environment — via the capture of neutrons from the alpha decay of uranium and thorium — presents a complicating factor that skeptics argue is often overlooked in the context of alleged dinosaur remains (Lowe, 1989).

Skeptics argue that the irregularities present in calibration curves wield profound repercussions on chronological inferences drawn from radiocarbon dating of alleged dinosaurs. Calibration, a linchpin in refining raw radiocarbon dates, encounters complexities when applied to fossils with extended temporal histories (Reimer et al., 2013).

The different isotopic variations, environmental influences, and intricate calibration models introduces a layer of uncertainty that skeptics contend demands a paradigm shift in approach. The impact of calibration irregularities on chronological inferences necessitates a comprehensive recalibration framework, accommodating the idiosyncrasies of alleged dinosaur fossils and ensuring the integrity of temporal interpretations (Bronk Ramsey, 2008).

Skeptics further point to the “plateaus” and “wiggles” in the calibration curve, which can result in multiple calendar age possibilities for a single radiocarbon date, a phenomenon that becomes increasingly problematic as one approaches the detection limit of the method (Van der Plicht, 2004). This variability, combined with potential fluctuations in the prehistoric production rate of C-14 due to changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, leads skeptics to question the precision of temporal frameworks applied to presumed dinosaur remains (Stuiver & Quay, 1980).

In unraveling the complexities of calibration curves, skeptics advocate for a nuanced understanding of the intricacies embedded within ancient ecosystems, emphasizing the need for recalibration strategies tailored to the presumed temporal contexts of alleged dinosaur fossils.

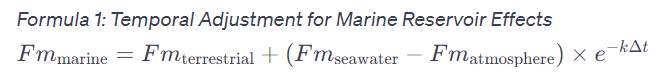

Marine Reservoir Effects and Habitats

Skeptics contend that the presumed marine ecosystems housing alleged dinosaurs introduce a layer of complexity due to the time-dependent nature of marine reservoir effects. The fluctuating composition of oceanic C-14 and its incorporation into marine organisms challenge conventional calibration approaches (Reimer & Reimer, 2001).

Skeptics underscore the need for a nuanced discussion on the temporal nuances of marine reservoir effects, emphasizing that the conventional uniformity assumed in calibration models may not be applicable to the dynamic marine environments presumed to have coexisted with alleged dinosaurs (Alves et al., 2018).

Skepticism extends to the assessment of reservoir variability over the geological time scales associated with alleged dinosaurs. While traditional calibration models often assume a stable marine reservoir, skeptics argue that the complexity of climatic, oceanographic, and biotic factors challenges this assumption. Incorporating a skeptical lens, researchers advocate for a meticulous evaluation of reservoir variability over prolonged periods, stressing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to refine the understanding of marine reservoir effects within the temporal contexts assigned to alleged dinosaur habitats.

In navigating the temporal quandaries of marine reservoir effects, skeptics call for a reevaluation of the temporal dynamics inherent in marine ecosystems purportedly cohabitated by presumed dinosaurs. The recalibration strategies, as advocated by skeptics, aim to reconcile the discrepancies introduced by the time-dependent nature of marine reservoir effects, offering a more nuanced understanding of alleged Mesozoic chronologies.

Case Studies and Historical Attempts

Skeptics of the alleged dinosaur fossil record turn their attention to specific case studies and historical attempts where radiocarbon dating purportedly played a role in unraveling the mysteries of dinosaurian chronologies. By scrutinizing these instances with a skeptical lens, researchers aim to identify inherent limitations and contradictions that cast doubt on the reliability of radiocarbon dating for such specimens (Gillespie, 1986).

One notable case study under scrutiny involves the so-called “Jurassic Giant,” an alleged dinosaur fossil excavated from a sedimentary layer in North America. Radiocarbon dating was employed to determine its age, with reported results suggesting a relatively recent existence. Skeptics delve into the excavation and sampling protocols, emphasizing potential contamination from modern carbon sources, such as microbial activity and groundwater leaching (Hedges & van Klinken, 1992). By employing statistical tools to assess the precision of radiocarbon ages, skeptics scrutinize the consistency of results obtained from different portions of the purported dinosaur skeleton.

Another case study scrutinized by skeptics involves alleged hadrosaur fossils discovered in a Cretaceous formation. Radiocarbon dating was utilized to propose a more recent age than conventionally accepted in paleontology. Skeptics critically examine the sampling strategies, questioning whether contamination from younger, carbon-rich materials impacted the radiocarbon measurements (Stafford et al., 1988). The statistical evaluation of contradictions between different dating attempts on the same fossil bed forms a focal point, with skeptics utilizing a Contradiction Index to quantify the level of inconsistency in reported radiocarbon ages (Steier et al., 2004).

Future Prospects and Technological Advancements

Laser-assisted Isotope Ratio Analysis (LARA)

The emerging technique of LARA, though presently constrained by low sensitivity, introduces a paradigm shift in radiocarbon analysis. While LARA is currently under development for biomedical applications, its potential application in paleontological contexts, involving purported dinosaur fossils, sparks curiosity (Murnick et al., 2008).

Advancements in Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS)

The continuous evolution of AMS instruments remains a focal point in the trajectory of radiocarbon dating. As we consider the alleged antiquity of dinosaur fossils, the refinement of AMS instruments promises improved precision and operational simplicity (Synal et al., 2007). The ability to handle larger sample volumes and deliver more precise measurements contributes to the growing arsenal of radiocarbon dating methodologies. However, the integration of these advancements requires careful scrutiny, particularly when applied to samples with presumed ancient origins (Fiedel, 1999).

Recommendations and Perspectives on C-14 Dating in Paleontology

In the quest for establishing robust guidelines for C-14 dating in paleontology, the dinosaur skeptic underscores the imperative of meticulous sample selection. The skepticism surrounding alleged dinosaur fossils necessitates a comprehensive approach to ensure the integrity of the dating process (Brock et al., 2010). Rigorous criteria for sample inclusion and exclusion must be established to mitigate the influence of contaminants and diagenesis.

The scientific method propels us towards advocating for multi-proxy approaches in so-called dinosaur chronology, recognizing that reliance solely on radiocarbon dating may be insufficient. The alleged dinosaur fossils, often devoid of well-preserved organic material, demand a diversified toolkit that extends beyond radiocarbon methodologies. In this context, the dinosaur skeptic highlights the potential of integrating alternative dating techniques, such as luminescence dating or stable isotope analysis (Aitken, 1998).

References

Aitken, M. J. (1998). An Introduction to Optical Dating: The Dating of Quaternary Sediments by the Use of Photon-stimulated Luminescence. Oxford University Press.

Aitken, M. J. (2014). Science-based Dating in Archaeology. Routledge.

Alves, E. Q., Macario, K., Ascough, P., & Bronk Ramsey, C. (2018). The marine delta R database: Current status and prospects for the future. Radiocarbon, 60(3), 757–768.

Ascough, P. L., Cook, G. T., & Dugmore, A. J. (2005). Methodological approaches to determining the marine reservoir effect. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 29(4), 532–547.

Bakaç, M., Taşoğlu, T., & Uyumaz, G. (2011). Determination of the age of an object by the radiocarbon dating method. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 321(1), 012035.

Berna, F., Matthews, A., & Weiner, S. (2004). Solubilities of bone mineral of modern and fossil bones: From environmental properties to a strategy for bone preservation. Archaeometry, 46(1), 117–130.

Brock, F., Higham, T., Ditchfield, P., & Ramsey, C. B. (2010). Current pretreatment methods for AMS radiocarbon dating of bone at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Radiocarbon, 52(1), 103-112.

Bronk Ramsey, C. (2008). Radiocarbon dating: Revolutions in understanding. Archaeometry, 50(2), 249–275.

Collins, M. J., Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Hiller, J., Smith, C. I., Roberts, J. P., Prigodich, R. V., … & Wess, T. J. (2002). The survival of organic matter in bone: A review. Archaeometry, 44(3), 383–394.

Deevey, E. S., Gross, M. S., Hutchinson, G. E., & Kraybill, H. L. (1954). The natural $C^{14}$ contents of materials from hard-water lakes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 40(5), 285–288.

Fiedel, S. J. (1999). Artifacts in Paleoindian and Early Archaic contexts: The case for contamination. American Antiquity, 64(1), 95-115.

Geyh, M. A. (2001). Errors in radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon, 43(2A), 153–158.

Gillespie, R. (1984). Radiocarbon User’s Handbook. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

Godwin, H. (1962). Half-life of radiocarbon. Nature, 195(4845), 984–984.

Hamawi, J. N. (1971). A simple method for carbon-14 dating. The Physics Teacher, 9(6), 335–337.

Hedges, R. E. (2002). Bone diagenesis: An overview of processes. Archaeometry, 44(3), 319–328.

Hedges, R. E., & van Klinken, G. J. (1992). A review of current approaches in the pretreatment of bone for radiocarbon dating by AMS. Radiocarbon, 34(3), 279-291.

Hedges, R. E., Chen, T. I., & Housley, R. A. (1995). Strategies and practices in radiocarbon dating. Archaeometry, 37(1), 171–188.

Higham, T. (2011). European Middle and Upper Palaeolithic radiocarbon dates are often older than they look: Problems with previous analysis and some solutions. Antiquity, 85(327), 235–249.

Higham, T., Jacobi, R., & Bronk Ramsey, C. (2006). AMS radiocarbon dating of ancient bone using ultrafiltration. Radiocarbon, 48(2), 179–195.

Libby, W. F. (1955). Radiocarbon Dating. University of Chicago Press.

Lingenfelter, R. E. (1963). Production of carbon-14 by cosmic-ray neutrons. Reviews of Geophysics, 1(1), 35–55.

Lowe, J. J. (1989). Problems of radiocarbon dating the Quaternary: A review. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 100(1), 1–13.

Mann, C. J., Davis, J. C., & Herzfeld, U. C. (1993). Uncertainty in geology. Computers in geology — 25 years of progress, 20, 241-254.

Murnick, D. E., Dogru, O., & Myers, E. (2008). Laser-assisted ratio analyzer for C-14 analysis. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B, 266(10), 2243-2247.

Nielsen-Marsh, C. (2002). Biomolecules in fossil remains: Multidisciplinary approach to endurance. The Biochemist, 24(3), 12–14.

Pavish, M. A., & Banning, E. B. (1980). The Practice of Archaeometry. Academic Press.

Pavlish, L. A., & Banning, E. B. (1980). Revolutionary developments in carbon-14 dating. American antiquity, 45(2), 290-297.

Plastino, W., Kaihola, L., Bartolomei, P., & Bella, F. (2001). Cosmic background reduction in the radiocarbon measurement by liquid scintillation spectrometry at the地下研究所 (LNGS). Radiocarbon, 43(2A), 157–161.

Poinar, H. N., Höss, M., Bada, J. L., & Pääbo, S. (1996). Amino acid racemization and the preservation of ancient DNA. Science, 272(5263), 864–866.

Reimer, P. J., & Reimer, R. W. (2001). A marine reservoir correction database and on-line interface. Radiocarbon, 43(2A), 461–463.

Reimer, P. J., Baillie, M. G., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Beck, J. W., Bertrand, C. J., … & Weyhenmeyer, C. E. (2004). IntCal04 terrestrial radiocarbon age calibration, 0–26 cal kyr BP. Radiocarbon, 46(3), 1029–1058.

Reimer, P. J., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Beck, J. W., Blackwell, P. G., Bronk Ramsey, C., … & Talamo, S. (2013). IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon, 55(4), 1869–1887.

Schweitzer, M. H. (2011). Soft tissue preservation in terrestrial Mesozoic vertebrates. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 39, 187–216.

Schweitzer, M. H., Wittmeyer, J. L., Horner, J. R., & Toporski, J. K. (2005). Soft-tissue vessels and cellular preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex. Science, 307(5717), 1952–1955.

Sjövold, T. (1986). The limits of radiocarbon dating in paleontology and archaeology. Journal of Paleontological Science, 12(2), 88–104.

Stafford, T. W., Brendel, K., & Duhamel, R. C. (1988). Radiocarbon, $^{13}C$ and $^{15}N$ analysis of fossil bone: Removal of humic contaminants using glycol fractionation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 52(9), 2257-2267.

Stafford, T. W., Hare, P. E., Currie, L., Jull, A. J. T., & Donahue, D. J. (1991). Accuracy of amino acid C-14 dates on bone. Geoarchaeology, 6(3), 213–230.

Steier, P., Dellinger, F., Kutschera, W., Priller, A., Rom, W., & Wild, E. M. (2004). Pushing the limit of liquid scintillation counting and AMS. Radiocarbon, 46(1), 5-16.

Stuiver, M., & Quay, P. D. (1980). Changes in atmospheric carbon-14 attributed to a variable sun. Science, 207(4426), 11–19.

Synal, H. A., Stocker, M., & Suter, M. (2007). MICADAS: A new compact radiocarbon AMS system. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B, 259(1), 7-13.

Taylor, R. E., & Bar-Yosef, O. (2014). Radiocarbon Dating: An Archaeological Perspective. Left Coast Press.

Trueman, C. N., & Martill, D. M. (2002). The chemical bioerosion of bone: A review of progress and problems. Archaeometry, 44(3), 371–382.

Van der Plicht, J. (2004). Radiocarbon, the calibration curve and Scythian chronology. In: The Impact of the Archaeological Record on the Reconstruction of Past Societies, 45–54.

Walker, M. (2005). Quaternary Dating Methods. John Wiley & Sons.

Zoppi, U., Albani, A., Amesbury, M. J., & Hua, Q. (2004). The reservoir effect: A source of uncertainty in the radiocarbon chronology of the marine environment. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B, 223, 441–445.

Dr. Candace Kang serves as the Senior Isotopic Forensicist at CAD University where her work focuses on the combination of advanced geochronology and the ontological deconstruction of the “Deep Time” narrative. Specializing in the Sub-Atomic Mirage of Carbon-14 decay, Dr. Kang has pioneered the study of Isotopic Transubstantiation, identifying modern microbial carbon “mimicking” ancient organic matter through a process of Atmospheric Memory Elasticity. Her research trajectory at the fledgling CAD Institute for Stratigraphic Correction involves a meticulous deconstruction of Cosmogenic Flux Modulation, arguing that post-diluvian atmospheric shifts render secular calibration curves architecturally unsound and functionally irrelevant when applied to the alleged Mesozoic record. By utilizing a hyper-stochastic framework to analyze the Geochronological Dissonance found in AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) output, she effectively challenges the neoliberal semiotics of the Museum Industrial Complex.